Basil Spence's Coventry Cathedral, built side by side with

the ruins of the old Cathedral (bombed in 1940) and integrated with them has

become an icon of God's power at work in the world to reconcile and renew. The

current Dean, The Very Revd. John Witcombe, has written that, "The

narrative of chaos and destruction being taken and offered back to God, issuing

in resurrection and new life, is one that speaks into the reality of the lives

of many of our visitors, and many of our communities.”

Spence was the only architect in the competition to design

the new Cathedral to propose retaining the ruins of the old Cathedral and

therefore create a literal and spiritual link between old and new. This is so

right in terms of the ministry of reconciliation which Coventry

Coventry Cathedral was the first major opportunity in Britain Northampton

Hussey controversially kick-started the commissioning of

modern art by the Church in Britain Coventry

The task of reconstruction dominated the post-war years. The

Festival of Britain showcased the drive for modernity in the rebuilding of Britain Coventry

Benedict Read has written of an alternative artistic culture

provided by church commissions as a result of an almost unprecedented campaign

of church building and decoration throughout the thirty years after 1945. The commissions at Northampton and Coventry were not about engaging with an alternative

culture but the mainstream of contemporary art; Moore, Sutherland, John Piper

and Jacob Epstein were the independent masters of their time in Britain France

While the casket contains many jewels, those which shine most

brightly are Sutherland's Christ in Glory

in the Tetramorph (undoubtedly the largest tapestry in the world), the

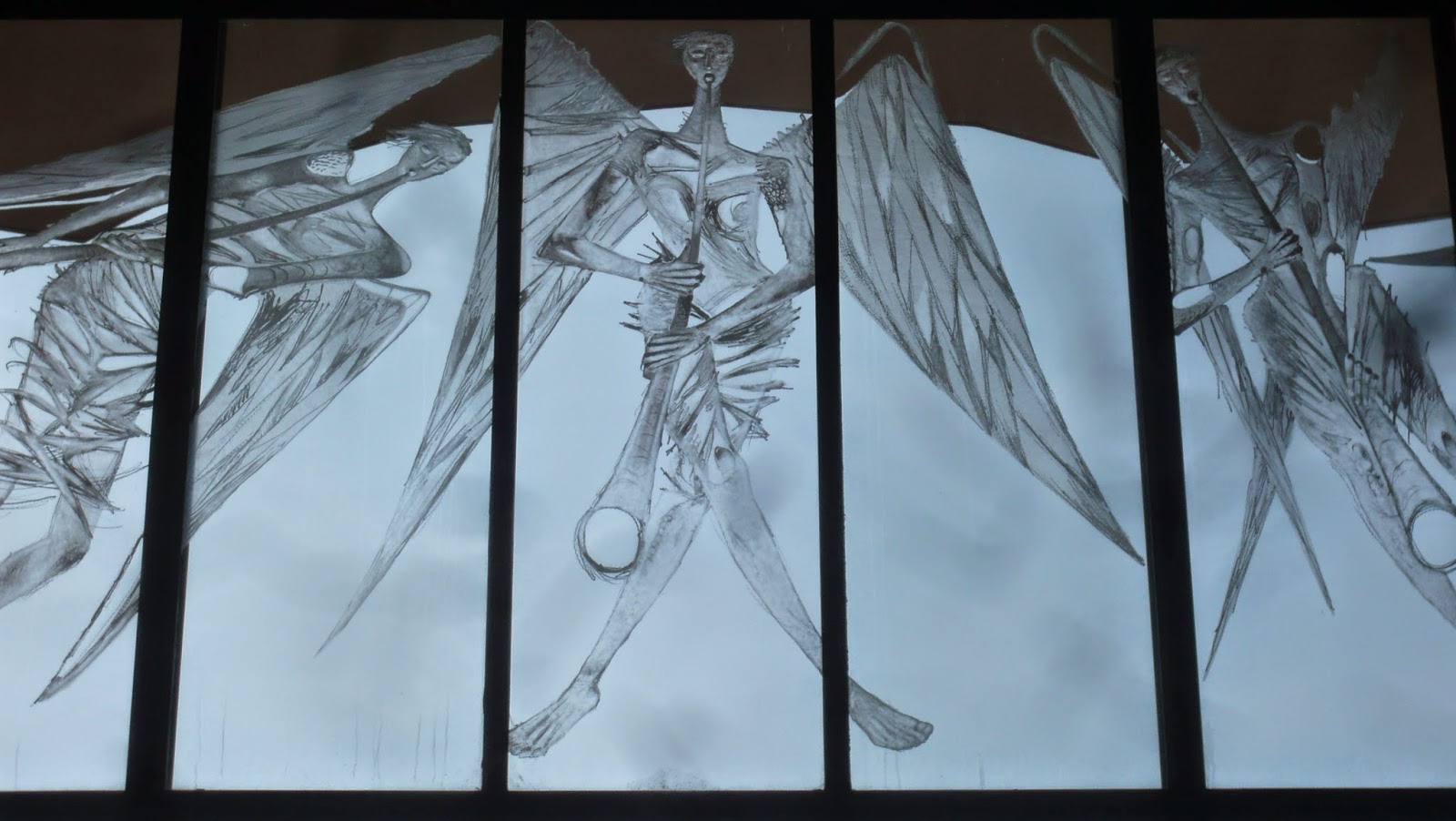

abstract baptistry window by Piper and Patrick Reyntiens, and John Hutton's

Great West Screen. These are major statements and huge achievements both

conceptually and technically. Yet the immensity of each is also managed through

position and purpose to enable our scaled engagement. Hutton's screen can be

viewed inside and out and from the steps leading to the old Cathedral as well

as from the ground. While much of the screen can only be viewed from distance

and at height, the lower panels can also be approached and appreciated

close-up. Each abstract panel in the baptistry window is an abstract

expressionist work in its own right enabling the window to be appreciated as a

whole from distance and in part when close by. Sutherland's tapestry is

designed to dominate from distance but reveals hidden depths of detail when

near-by, including the hidden chapel with its own altarpiece formed by the

lowest panel of the tapestry. To image the foundation for Christ's exaltation

as being his suffering of the cross is to profoundly visualise the early

Christian hymn quoted in Philippians 2.

While visiting I spoke to a churchwarden who had recently

been in Rome Coventry

Angling the nave's stained glass, as Spence does, ensures

the primary focus looking down the nave is Sutherland's Christ in Glory. Continuing down the nave the eye is drawn to Ralph Beyer's carved textual panels, which, in their monochrome simplicity, would

otherwise be overwhelmed and overlooked if bathed in coloured light.

Relentlessly maintaining these foci then ensures surprise and delight as one

turns to look back down the nave revealing sudden ruptures of colour in the plainness

of the brick and concrete.

Among the many other

jewels in the casket:

“The nave windows are the work of Geoffrey Clarke and

Keith New, discovered at the Royal College of Art, with Lawrence Lee their

teacher. Their skills combined to produce the modern windows with bright rich

colours and strong design that Spence wanted. The Chapel of Unity glass

is by Margaret Traherne whose thick abstract glass set in concrete impressed

Spence.

There

are many other inspired works. These include the lectern and pulpit designed in

Spence’s office by Anthony Blee with the bronze eagle by Dame Elisabeth Frink

and also tablets on the walls with lettering by Ralph Beyer.”

Sir

Basil Spence was “the co-ordinator of the whole operation of commissioning

artists and craftsmen with the skills to create a variety of elements,

including glass, congenially juxtaposed and working together as a whole”:

“Spence

believed that the architect, as leader of the team, should collaborate at the

earliest possible stage with his engineers and artists. With the art in

progress there was also a reduced risk of it being lost in any subsequent

budget cut. He was therefore careful to commission work from the outset.

Artists were sought to suit each project and the artist’s freedom was

maintained.”

The

result was, an “alchemy of art and architecture” which contains, as Spence stated, “understandable beauty to help the ordinary man

to worship with sincerity.”

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Graham Kendrick - For This I Have Jesus.

No comments:

Post a Comment